Dysfunctions of Multi-Discipline Teams

Back in the summer of 2001 I started my first role as a Software Engineer. This role had a wide range of responsibilities that included gathering requirements, designing the User Interface and producing quality code to meet the user needs. We also had to design our own windows program icons, which resulted in some very peculiar works of miniature art!

One of the downside of this job is that, although we were organised into teams, we worked alone. The teams were just amalgamations of individuals brought together to share common line management.

Fortunately, the industry has moved towards a more collaborative approach to building software, with many teams now working together to solve problems. But this has also resulted in a wide range of additional roles becoming common within the workplace. Some of these roles are specialisations of activities that may have been performed by Software Engineers (e.g. Business Analysis, Testers). Other roles have appeared due to advances within the industry, Data Scientists and User Experience (UX) are examples of this.

The end result of this is the multi-discipline team. A collection of individuals with a range of skills required to meet the customer need. There are obviously many benefits to having this range of skills, such as not having my terribly designed windows icon. But there can also be a wide range of problems, or dysfunctions of a multi-functional team. This post will examine three and provide advice about avoiding these pitfalls.

1. Bottlenecks

Having a single expert in a certain skill will create bottlenecks in the flow of work through the team. For example, a single person responsible for testing will mean that inventory (AKA work) will stop if this person becomes busy or unavailable. This will increase the lead-time of delivery of features to the customer. Furthermore there can be delays in feedback for the team; an example is engineers being interrupted to fix issues that the tester has found in code they completed several days earlier.

The key to avoiding this problem is building redundancy into the system. The simplest mechanism to do this is to not have a single person in any role in the team, so multiple Testers, Business Analysts (BA) etc. Wage cost and inefficiencies through underutilisation makes this an unappealing solution for most organisations.

Some attempt to work around this by having separate teams of experts who are parachuted into teams when required. This often results in a Tragedy of the Commons with the team of experts becoming fought over by teams that need help at the same time. It can be argued that this structure loses many of the benefits of a multi-disciplined team, such as collective ownership of the product(s).

A preferred mechanism of introducing this redundancy is to reposition these roles as consultative rather than being the sole practitioner. For example, you may have an expert Tester on the team but part of their role is to ensure that anyone on the team can pick up testing if required. In other words, they are responsible for driving the approach to testing NOT being the single person who tests the code. But what do they do with their free time? Maybe pair with an engineer on some code, or use the skills the expert BA has imparted to speak to a client about their requirements.

2. Dysfunctional Communication

Multi-discipline teams are generally larger and as such have a much greater number of internal communication points and routes than smaller teams. The difference in language from the different professional domains may also cause miscommunication. For example, the terminology of a User may be subtly different between BA, UX and Engineers.

Communication outside the team may also be complex, particularly in larger organisations where team-to-team communication might be carried out on role-to-role basis between externally facing roles. Project Managers talk to Project Managers; Product Managers talk to Product Managers etc. This can lead to external communication between Engineers, Testers or others having to pass through these people. Anyone who has played the parlour game Chinese Whispers (or Telephone Game in US) will know the inevitable consequences of this.

The easiest way of combating these communication issues is to limit the people and roles in team to those that are essential. Often organisations have a template of what a team should look like, such as a Product Manager, UX, BA, Tester and Engineers. Consider whether you really need all these roles to meet your user needs. Fixating on particular job titles may also miss opportunities to employ individuals with multiple skill sets who might help bridge the communication divide.

To avoid Chinese Whispers all team members should be encouraged where necessary to engage in external communication. The caveat to this is that the rest of the team should be kept informed of what was discussed and any decisions that are made. Some teams use some form of lightweight decision records to document such findings.

3. Conflicting Objectives

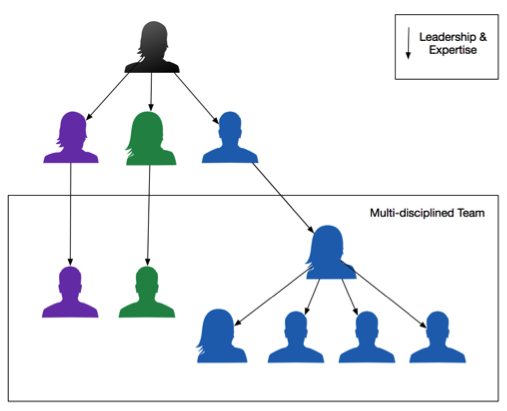

The introduction of different roles into teams has brought with it questions about how to manage and develop these individuals. Traditionally, management is based upon both leadership and expertise. For example, as a tester you’d be managed by someone who was once was a tester. This seems fairly rational, as the manager would be able to impart his or her own learning’s and empathise with the individual.

Applying this logic, this can lead to a management structure that might resemble the diagram in fig 1. Each of the coloured silhouettes in this diagram represents a different discipline.

fig 1

The challenge with this structure is it likely to result in conflicting objectives within the multi-disciplinary team. An example of this would be if the manager of UX decides that the most important objective is delivering consistent look and feel across the products, where as the superior of the engineers feels that the number one objective is moving services to the cloud. With team member’s success and possibly bonus being measured on these objectives it is possible that conflict will develop within the team.

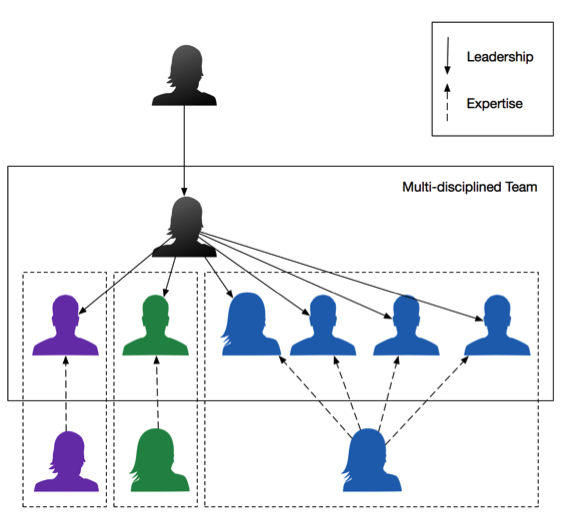

Unless you’re Hitler, who used conflicting orders and subsequent infighting to maintain his absolute position at the head of the Reich, you probably want to avoid this. An ideal solution is to change the structure of organisation to separate leadership from expertise. One approach to this is to create discipline or chapter leads as shown in fig 2. These people are simply the most experienced practitioner of their disciplines and may just hold a day job as a member of this or another team. This allows leadership decisions to flow through a simpler more direct direction.

The head of the team I have purposely left an unspecific black, as this person could be from any discipline. Some teams may not even need this specific role if the strategy and OKRs from above are good enough.

fig 2

Of course most people are not in control of re-organising your workplace, so what can you do to avoid these conflicting objectives? One approach is to have completely transparency on objectives within the team, so that you can spot conflicts and resolve them earlier. So in our previous example, the team can mix the work to provide a consistent look and feel with the work to move to the cloud – perhaps there are opportunities where they can do both. Or if they are not as easy to reconcile this can be jointly fed back up the management chain.

Conclusion

Having a wide range of skills within the team can be extremely beneficial to the quality and effectiveness of your product. Having this array of disciplines can also have a cost in terms of communication and production bottlenecks.

So, it is important to understand which skills you need rather than following a boiler-plated ideal of what a development team should look like. Furthermore, specialists within the team should be consultants, helping to spread knowledge of their disciplines. Thus minimising the risk of production bottlenecks.

Communication should be encouraged throughout the team and where necessary directly with external parties to avoid Chinese Whispers. It is also important to fully communicate any discipline specific objectives to ensure that team members are not working against one another.